Macular Degeneration: What You Need to Know

Macular degeneration (AMD) can be a visually devastating disease. It can affect our grandparents, our parents, our aunts, uncles, brothers, sisters and friends. It is the leading cause of blindness in those over 65. America’s aging population is growing rapidly and AMD affects 10-15 million of these patients today. It is projected to affect 20-25 million in 2020.

Who’s at Risk?

Age is the greatest risk factor for developing AMD. White females have a further elevated risk, as do patients with a family history, who smoke, and who have light iris color. Some studies also show that high blood pressure, obesity and inactivity can worsen the disease.

What is AMD?

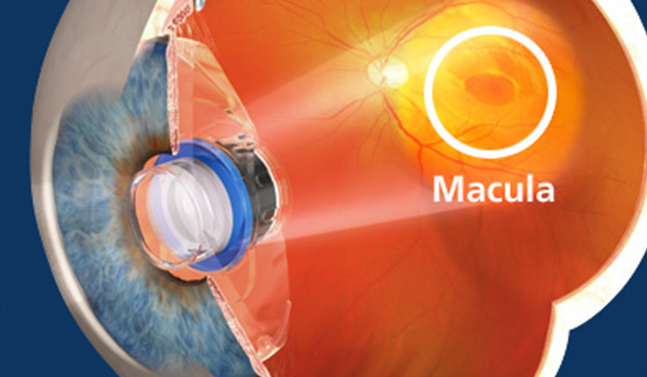

AMD is a retinal disease. It causes nerve cells in the center of the retina (macula) to die. The patient loses the ability to see fine detail, develops blind spots, and can ultimately lead to complete central vision loss . It is diagnosed as either dry or wet. The dry form is more common than the wet form, with about 85 to 90 percent of AMD patients diagnosed with dry. The wet form of the disease usually leads to more serious vision loss.

What is the treatment?

No FDA-approved treatments exist yet for dry macular degeneration, but over-the-counter retinal multivitamins (AREDS & AREDS 2 formulations) may help prevent its progression to the wet form. For wet AMD, treatments are aimed at stopping abnormal blood vessel growth and include drugs called Avastin, Lucentis, Eylea, Macugen and Visudyne used with Photodynamic Therapy or PDT. These treatments have been shown to control disease and can improve vision in a significant number of patients. Unfortunately, injections into the back of the eye may need to be repeated for months or years.

Recent developments show additional promise in aiding the many patients who suffer from AMD. I came across two recently published studies regarding AMD therapy. The first study looked at an oral medicine called AZT. This medicine has been used for decades to treat patients with HIV, has a good safety profile and is inexpensive. It was shown to effectively block AMD in laboratory mice. It controls a molecular inflammatory cycle and works well on human retinal cells in the laboratory.

The second study reported results of a novel lens implant system that can be used at the time of cataract surgery. The mini-telescope system involves the insertion of two separate lens implants into the eye in a ‘piggyback’ fashion. Each is foldable and can be injected through a small incision. The anterior or ‘sulcus’ lens is a high-plus power lens, while the posterior or ‘in-the-bag’ implant is a high-minus power lens. This set-up leads to high magnification, which spreads the vision over a larger surface area of retina to increase vision. This system is not available in the United States, but has been implanted in over 100 patients by the author of the report (in London).